“It isn’t all over; everything has not been invented; the human adventure is just beginning.” [1]

In the final episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, “All Good Things…,” Captain Jean-Luc Picard is sent on a journey, back and forth through time, by the omnipotent, god-like being, “Q.” To save humanity from a massive “spatial anomaly” threatening Earth in three different time periods, Picard must play Q’s game. In a scene from Picard’s past, he relives his first day aboard the Enterpise, the Federation’s flagship. Approaching the craft in a space shuttle, Picard sees the Enterprise “for the first time.” His reaction, along with the shuttle’s pilot, is one of awe – a terror of the sublime, like that which sixteenth-century European explorers or nineteenth-century American painters expressed when viewing the natural landscapes of the North American continent. Thomas Cole, the great painter of the Hudson River School, was representative of this nineteenth-century American attitude when he said “Nature has spread for us a rich and delightful banquet. Shall we turn from it? … We are still in Eden. The Wall that shuts us out of the garden is our own ignorance and folly.” [2]

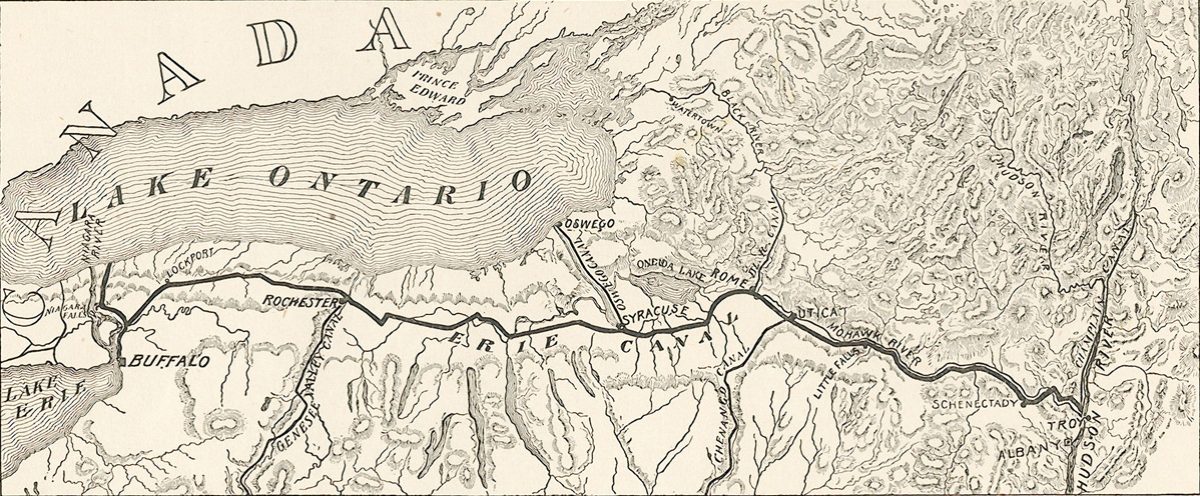

Picard’s reaction is in this same vein and reflects Star Trek’s universe as well. In the twenty-fourth century, technology has severed humanity from the limitations we know today. Space and time have been redefined. Our values and abilities have changed. Technology created a new frontier, a supposedly final frontier. But historians know this frontier is nothing new. Humans have experienced the “frontier” throughout history, the most memorable being the “New World,” “discovered” by European explorers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and, for the United States, the great Western frontier which defined the nation’s identity and culture for at least its first 100 years. [3] While frontiers have meant different things to different people’s throughout time, for the modern western writers and producers of Star Trek, these two examples were probably the most relevant. Picard’s insignificant scene reveals much about the universe Gene Rodenberry, series creator and producer, developed. Among others things, it betrays a modern, technocratic world-view, an optimistic belief that technology will allow humanity to survive the contemporary existential threats of climate change and technological apocalypse. [4]

Through Star Trek: The Next Generation, Gene Rodenberry created a universe vastly different from our own and yet still human and relatable. The universe inhabited by Jean-Luc Picard, Will Riker, and Jordie LaForge projects late twentieth-century American values onto a futuristic utopia where humans survived technological adolescence to explore the Milky Way Galaxy. Roddenberry’s universe is what acclaimed environmental historian, Donald Worster, referred to as the illusive “Third Earth,” a new frontier, which when combined with human technological prowess, allows for infinite growth. The world-view of the Enterprise’s crew, born of 1980s and 1990s U.S. American culture, makes complete sense: it reveals a future in which technology has overcome nature, both human and non-human. Through advances in science and technology, humans unbound themselves from the limits of growth, the economic catastrophe so feared by American producers and consumers intensifying in the second half of the twentieth century. These developments enabled people to overcome our moral, philosophical, and physical shortcomings to avoid apocalypse, environmental and social, and create an economy of infinite, sustainable growth. Inventions such as the warp drive, transporter, and replicator, all annihilated space, time, and the limitations of capitalist accumulation.

The Next Generation story is decidedly optimistic, displaying a culture which ended poverty, war, and most disease. In fact, technology allowed for a society without money; an economic system of unlimited growth without capitalist accumulation and the environmental and social destruction that goes with it. This is the fundamental flaw of Roddenberry’s utopia: it takes a “pro-growth,” “cornucopian” view of economy and resource use, placing complete faith in technology, without questioning or re-evaluating capitalism, the ideas which encompass it, or the moral conundrum of unbridled accumulation. Technology in the twenty-fourth century creates new efficiencies that allow for infinite growth in a seemingly sustainable manner, and thinking about this future-society from the early twenty-first century helps shoulder the moral and ethical burdens of unquestioning loyalty to the capitalist ideal.

Perhaps this is one reason for the show’s immense popularity. Perhaps late twentieth-century fans saw this utopia for what it was: a relatable, easily swallowed vision of our future, where capitalism continues but in a sustainable way. Technology is king and has solved most human problems, environmental, social, economic, and political. We do not need to consider alternatives to capitalism, the religion of growth, or our modern faith in technology, science, and expertise to master nature and solve all human problems. According to Sebastian Buckup, member of the Executive Committee of the World Economic Forum and science fiction commentator, good science fiction combines “great science” and “a keen understanding of contemporary hopes and fears.” Using this definition, Roddenberry is a good science fiction creator. The universe of Star Trek presents a society that has solved almost all of the social, environmental, economic, and political issues of the twentieth-century, and human’s have done it by remaining loyal to capitalism, technology, and confidence in human ingenuity. [5]

Roddenberry, a self-styled humanist and agnostic, called himself “a complete pagan,” referred to pious Christians as having a “substitute brain… and a very malfunctioning one,” and stating that “contemporary Earth religions would be gone by the 23rd century.” These beliefs, combined with his law enforcement, military, and engineering background, illuminate the forces influencing his construction of the Star Trek narrative. A believer in human intelligence and ability, an advocate of science, law, and order, and a devotee of progress through expert knowledge, Roddenberry was a typical, mid-twentieth-century modern American man and he projected this onto his utopia, exposing an understanding of American “hopes and fears,” as well as in “great science. [6]

Science fiction is an important part of human cultural history in the twentieth-century. During an October 2016 presentation at the Anarres Project Conference, sponsored by the Ohio State University Honors College and College of Science, Dr. Randall Milstein discussed “the cultural and technological impact Star Trek has had on society and everyday life.” Building on a dearth of other humanities scholars, Milstein argues “science fiction” is a vital part of popular culture, creating many of the central modern myths of Western culture. It influences how our culture “views technology and relates to technology in our contemporary world.” Shows like Star Trek influence people who move into the science professions, like Bill Nye and Neil Degrasse Tyson. Milstein states “science fiction is the literature of human society encountering change” in environment, technology, and human relationships. Further, books, magazines, television shows, and movies influence engineers and planners, as well as “our general ‘cultural zeitgeist’ and attitudes toward the future.” In this way, the science fiction of “today,” in many cases, becomes the “science” of tomorrow. This relationship between public planning, “cultural zeitgeist,” and science fiction, reveals one reason why Gene Roddenberry’s vision of the future is so important: science fiction demonstrably influences contemporary engineering, science, policy, and planning, as well as cultural attitudes towards the future. If Star Trek does not question unbridled capitalist accumulation, infinite growth, would many twentieth-century United States citizens do the same? Or would Star Trek offer a convenient outlet for anxieties about approaching scarcity, allowing Americans to avoid the difficult conversations around capitalism, natural resources, and environmental decline? [7]

As with Mary Shelley and Frankenstein, or Jules Verne and Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, or Ray Bradbury and The Martian Chronicles, Gene Roddenberry reflected American cultural aspirations and fears through an absolute faith in science and technology to solve human ills showed in the Star Trek universe. In fact, the back-story of the Star Trek universe itself fulfills this narrative. Star Fleet, Earth’s governing body for space exploration, reigns over a world that survived apocalypse, world war, and climate crisis. This factor alone is an optimistic projection of the future, where we have survived the failings of a modern and capitalist society. While many in the late twentieth-century began to realize this potential catastrophe waiting along the horizon of capitalist accumulation, Roddenberry’s vision was that of most Americans: a vision of capitalism-as-savior, a blind-faith in “progress” and “growth,” an irrational denial of the unsustainable nature of some core ideologies of our society.

In his 2016 book Shrinking the Earth, Donald Worster tells the story of abundance in American history, and really, global history. In many ways, our current age of climate change began where Worster’s story does: with a Europe in crisis, severely short of resources, unable to withstand the population increases of recent centuries. And then, a moment of divine intervention: the discovery of the New World, or, as Worster calls it, “Second Earth,” that new frontier which “ushered in an age of unprecedented material abundance,” inundating older civilizations with new natural resources and “the freedom those resources made possible.” [8] The discovery set off many changes, some revolutionary. The most important, according to Worster, related to abundance and a new possibility that Europeans had found unlimited growth potential. Called the “theory of the greenlight,” the theory states that “the discovery around 1500 AD that the earth has an entire Western hemisphere of immense continents and oceans marked a watershed in human experience.” It started the modern era, an epoch where “the wealth of nature,” when “appropriated and turned to use,” began a series of revolutions in science and technology, and commerce, politics, and society, not to mention in the relationship between humans and the natural environment. Perhaps more importantly, it triggered a “shift in perception,” for a time “congruent with the material” changes also occurring. Worster warns, as critics since in the early twentieth-century have as well, the “modern era of extraordinary natural abundance” was coming to a violent, jarring end. Neither science, technology, or pure human ingenuity could “bring it back.” At the beginning of the twenty-first century, once again, human kind faces “an adjustment of ideas, institutions, and ecologies of global proportions.” If we do not change, we face catastrophe. [9]

Worster use biographical sketches of humankind’s great scientific, economic, and philosophical minds to illustrate the evolving relationship between abundance and scarcity in Western thought, beginning with the discovery of the New World. Through individuals like Gerard and Rumold Mercator, Guillame-Thomas Raynal, Nicolas Copernicus, Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, Charles Darwin, John Stuart Mill and many other scientists and scholars, Worster unveils the tension between accumulation and sustainability apparent throughout Western history. He shows that mainstream views of “infinite growth” were challenged, but never overtaken, by fears of scarcity and ecological degradation. For example, Worster deftly analyzes Rumold Mercator’s 1587 map which first imprinted the idea and image of “second earth” in people’s minds. The younger Mercator’s document was highly influential to how Europeans imagined the New World, human’s relationship with the environment, particularly natural resource use, and served as an almost booster-like document for pro-growth, imperial tendencies. [10]

The religion of growth entrenched in twentieth-century society, the U.S. in particular, can be traced to the discovery of the New World. Over the course of centuries, the old-world “sense of the land’s limits” [11] gave way to a firm, optimistic faith in future growth. Descriptions of America show what “second earth” represented to Europeans. Dutch colonist Adriaen Van der Donck described “the superabundance” of the new nature in 1655, confidently stating it was “not equaled by any other in the world.” [12] Guillaume-Thomas Raynal, the radical French priest, saw “revolutions occurring in commercial networks and state relations, in social thought and social order.” The first great leader of the scientific revolution, Nicolas Copernicus, likewise thought Second Earth was a boon to his “investigations into the heavens.” So much of Copernicus’ work, as well as that of men like Charles Darwin, and so much of “modern scientific inquiry, with its devotion to collecting new facts and organizing them into theories,” came following “that extraordinary event.” [13]

A happy faith in increasing productivity, the basic core doctrine of modern capitalism, modern economics, and neoliberal theory, appeared slowly after Europeans found “second earth.” But beginning with Adam Smith, who believed wealth the accumulation of “all the necessaries and conveniences” of human life, and continuing with men like Thomas Malthus and David Ricardo, a continuous tension between abundance and scarcity has plagued western society, one that brings us to the brink of catastrophe in the early twenty-first century. By the early twentieth-century, miners in the American West and others around the world, claimed “isolated lands” would be “great empires,” whose inhabitants held “the key to a vast vault, filled full and running over with previous treasures, and to a still vaster land, ‘flowing with milk and honey.” [14] While the “pro-growth coalition,” represented by men like Henry Charles Carey and Andrew Carnegie, became universal throughout the world, specifically in the United States during the twentieth century, others like The Limits to Growth authors Donella and Dennis Matthews, saw the writing on the wall and knew infinite growth was impossible, illogical, and irrational. [15]

Worster also uses the more recent example of noted scholar and historian, Walter Prescott Webb, to show the deeply embedded nature of the capitalist worldview as well as the emerging public acceptance of a limit to growth. Webb declared the new world bounty a “windfall.” He believed “…without that discovery [second earth]…,” no nations would have been “jolted into reorganizing their institutions and cultural attitudes.” But Webb was a man of the later twentieth-century, and he knew humans faced a reckoning in the near future. “The land, wrote Webb, “has only so much to offer…There is a limit beyond which we cannot go; and if our techniques speed up the process of utilization and destruction, as they are now doing, they hasten the day when the substance on which they feed and on which a swollen population temporarily subsists will approach scarcity and exhaustion.” Worster seamlessly narrates the long evolution of human ideas of scarcity and abundance, revealing how twentieth-century environmental destruction began to shift the conversation away from assumed infinite growth to cautious resource restraint.[16]

With the development of the ideals of “conservation defined as development,” and “protecting nature” being “a role that government was equipped to perform very well,” Americans like Theodore Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot, and William John McGee touted the new economic and environmental system as seeking “the greatest good for the greatest number of people for the longest time,” or as Gene Roddenberry might call it, “infinite growth.” A new dogma of planning would lead to a society which protected its natural abundance and strived for a “techno-industrial” civilization which would raise living standards and personal and societal growth and accumulation. As the decades passed, the United States “conserved” more and more of its lands, waters, airs, and resources, leading to a further improved, mastered, and utilized environment. Pollution and consumption reached historic levels, and the “Great Acceleration” pushed our species closer to apocalypse than ever before. Some scholars, planners, and politicians, fearful of a race to scarcity, began speaking out in larger numbers. Fairfield Osborn, Jr., William Vogt, Marion King Jubbert, of Shell Oil, and John Kenneth Galbraith, of Harvard University, among others, began forcefully speaking on the issue Samuel H. Ordway, Jr., a New York lawyer and Businessman, and briefly in the 1960s, president of the Conservation Foundation, called “a theory of the limit of growth.” Resistance to the pro-growth coalition and their “religion” of unlimited accumulation coalesced in reaction to the Paley Commission’s decidedly capitalist interpretation of environmental issues and around publications like Harold Barnett and Chandler Morse’s Scarcity and Growth: The Economics of Natural Resource Availability, or Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, or Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, or Barry Commoner’s The Closing Circle and Science and Survival. All these books spoke to different aspects of the “limits to growth” issues, reactions to “the postwar period” and “a time of intensified plundering in the pursuit of plenty”: some spoke of population, some of ecology, some of unrestrained agriculture. They all emphasized the unsustainable nature of our current economic, political, and environmental systems. A new cry replaced conservation in reaction to issues of abundance and scarcity: the modern environmental movement.[17]

This “new” environmental movement took the warnings of a limit to growth seriously, climaxing with the release of The Limits to Growth in 1972 by Dennis and Donella Meadows, a married couple of upper, middle-class PhD students who, after visiting India in the summer of 1969, became convinced that humanity was on a path of no return, where our world would become uninhabitable if we did not change our consumptive ways. Limits to Growth “expressed better than any of its predecessors a deep cultural transformation going on that would become unstoppable over the decades to follow. It was the book that cried wolf.” [18]

Reactions to the book were, unsurprisingly, uncritical and harsh. Modernists and capitalists, economists and politicians alike, all often “did not read the book carefully or treat it with the respect they might have given to one of their own.” Carl Kaysen, an influential economist and adviser to President John F. Kennedy said, in one of the more positive reviews from an economist, “the problems they call us to attend are real and pressing. But none are of the degree of immediacy that can rightly command the urgency they feel.” In the New York Times Book Review, three economists, Peter Passell, Marc Roberts, and Lenoard Ross, did not even try “to dig in to the book’s complex arguments,” but simply tossed it aside as “an empty and misleading work…Garbage In, Garbage Out.” Conservative economist Henry C. Wallich, a regular writer for Newsweek, denounced the book as “a piece of irresponsible nonsense.” The book was considered so reactionary, Yale professor William Nordhaus sneered at it for predicting “an end to the economic progress that the West has experienced since the Industrial Revolution.” Such respectable names and scholarly reputations lent credibility to these uninformed opinions. The public heard them and many believed them. [19]

But the issue of scarcity did not go away. In fact, the calls for reconsidering capitalism and unlimited growth only grew in volume and intensity. Earth Day, 1970, was an important symbolic event, showing that humanity was aware and worried about the environmental problems facing the world. Ecologists, environmentalists, historians, and anthropologists, all used their scholarly soapboxes to preach the issue and bring attention to the prodigious amount of work being produced by academia. While pro-growth forces definitely “won” the growth debate during the 1960s and 1970s, the environmental movement has only continued gaining steam, surviving both the Reagan and Bush administrations, and now the Trump administration’s hostility to environmental regulation and ideas questioning the supremacy of the free market and capital accumulation. In 2019, environmental issues are considered by many to be the most dire humanity faces today. The emergent anti-intellectual, populist movement of the early twenty-first century notwithstanding, the “limits to growth” crowd, and their efforts, must be considered at least some what of a success. Their arguments about abundance and scarcity, in the end, have proven correct. We face the ultimate test of modern civilization: we must chose between accumulation and restraint, “freedom” and regulation, if we, and our planet, are to survive. [20]

This is the ideological landscape historians must view Star Trek: The Next Generation in. Americans in the 1980s and 1990s largely learned for the first time about many issues of environmental crisis and injustice, including the OPEC Oil Embargo, Love Canal, Three Mile Island, the hole in the ozone, and climate change. As Americans have slowly realized the dire nature of the situation, Star Trek stands as a vision for the future for many of us. The show’s popularity gave Gene Roddenberry a powerful voice in articulating what kind of future humanity can have.

By following specific people to trace human ideas of abundance and scarcity, Worster provides an excellent picture of human’s evolving historical relationships with technology, science, nature, and resource-use. Situating Gene Roddenberry’s utopia of infinite growth within this framework becomes simple. In the face of catastrophic resource shortages in the energy industries, ever increasing levels of industrial pollution, and new theories of global climate change quickly gaining mainstream credibility, Star Trek provided Americans an optimistic image of the future, where science and technology solved all of our problems, allowing humans to continue our faith in infinite growth without questioning our seemingly innate desire for culturally constructed ideas like “progress” and “growth.”

“Ancient astronauts didn’t build the pyramids. Human beings built the pyramids, because they’re clever and they work hard.” [21]

Star Trek: The Next Generation follows the crew of the Enterprise through their exploration of the galaxy, in times of peace and war. Ignoring the racial and colonial undertones of the “prime directive” and Starfleet’s overall political and economic goals of expansion, the entire purpose of the Enterprise is to “seek out new life and civilization; to boldly go where no one has gone before.” Science and technology will take us there. Throughout the series, Roddenberry’s episodes flesh out the utopia of infinite growth he foresees in the future. Plot lines and character developments revolve around the relationship between humans, technology, and control of the natural universe. By analyzing specific episodes, one illuminates Roddenberry’s underlying faith in capitalism, human ingenuity, and a technocratic society. His utopia is a technological one, where human invention has obliterated limitations to progress and created a sustainable society in which humans can thrive and accumulate “wealth” (a wealth foreign to our sensibilities, as there is no money in Roddenberry’s twenty-fourth century). Although not a completely uncritical commentary on capitalism, growth, and the future, nonetheless, Roddenberry was a loyal “Copernican” and “pro-growth” partisan, projecting confidence in expert scientists, engineers, and planners to mold society for sustainable, infinite growth. By creating such a Utopian vision, Roddenberry was, in effect, telling Americans they could dream of the future without needing to analyze capitalism and its destructive tendencies. Technology and human creativity were sufficient to restructure capitalism, leaving intact its core ideals of growth and progress, and create a sustainable society.

Roddenberry uses specific innovations to most effectively convey his belief in technology’s ability to better the human condition and create a sustainable civilization. Replicator, Transporter, and Warp technology all changed human society in fundamental and interconnected ways. Their use literally obliterates the limitations of time, space, energy, and resource accumulation for humans as they expand throughout the galaxy. Take the commonplace technology of the transporter. Severing humans from the constraints of physics, the transporter allows humans to travel, instantaneously, from place to place, without the need of conventional forms of energy or machine. In times of crisis, the Enterprise can transport people away from danger. Whether it be an away team surveying the surface of a dangerous planet, or an entire civilization in need of rescue from planetary catastrophe, the transporter allows humans, and their cargo, to cross vast distances almost instantaneously.

While its use creates moral and ethical quandaries of its own (flesh and bone are annihilated and then reassembled), transporter technology allows humans to overcome physical nature, energy demands, and time constraints. In the episode “Realms of Fear,” Roddenberry goes further and details the transporter’s, and by extension science and technology’s, mainstream adoration in twenty-fourth-century society by showing the scorn and public shame felt by crew members who fear using the transportation infrastructure. While investigating a transporter accident (oh, the irony!), a crew member reveals his fear of using the technology, which leads fellow crew-mates to question his sanity. Their blind acceptance of transporter use shows not only that it is extremely useful and effective, but that it is trusted. Every person using the transporter submits their body to death, only to be reborn on the other side of their journey. Think of the changes in the way humans relate to nature needed for this matter-of-fact acceptance. What does it mean? Technology is key to society’s survival in the vast universe. Without it, sustainable life, with high living standards, would not be possible. [22]

Even more integral to Roddenberry’s universe were warp and replicator technology. Warp drive allows travelers to reach speeds approaching that of light, bending space and time to allow transit across vast distances in relatively minuscule periods of time. The implications for this technology are obvious, but when we focus our analysis on human relationships with nature, the implications become much more illuminating. With the ability to travel to distant worlds, warp drive enables humans to seek out new homes when their environments have been degraded. We see this in a number of episodes and are also introduced to a history of space colonization made possible by warp technology.

In “A Journey’s End,” the Enterprise is dispatched by Star Fleet to “resettle” a group of Native Americans due to a peace treaty with the alien race of Kardassia. This group of humans searched for a home beyond Earth for decades, finally settling on Dorvan V, only to be forced to leave twenty years later. While also a critique of colonialism, this episode does not question technocratic culture and supports a future utopia of abundance made possible by warp technology, giving humans the ability to leave a planet when all resources are used or it becomes uninhabitable.

In a further example, “Up the Long Ladder,” the Enterprise rescues an Irish colony facing planetary collapse. They are “resettled” on a new planet, possible only because of warp technology. With the ability to cross the galaxy, like nineteenth-century Americans crossing the North American continent, humans in Gene Roddenberry’s utopia of infinite growth live in a reality where planet-wide apocalypse can be survived. With this new technology, what need for sustainable environmental practices emanates from society’s economic systems? [23]

The most integral technology for understanding Gene Roddenberry’s utopia of infinite growth is the replicator, which can “reconstitute matter and produce everything that is needed out of pure energy, no matter whether food, medicaments, or spare parts are required.” It can create any inanimate matter, as long as the desired molecular structure is known to the computer. The replicator’s importance is, like warp drive, very apparent. Without the need to grow food, collect resources and energy, or labor to build and maintain things, an economy of growth is far easier to obtain and a sustainable system is much more easily grasped. Without these needs, human’s can live in more diverse environments, avoiding the need to locate communities where resources are abundant and allowing for longer travel to more distant places. Combined with the transporter and warp drive, the replicator shows how humans have been further disconnected from nature in Roddenberry’s universe. Like twentieth-century consumers detached from the labor and geography of the calories they eat, human’s of the future have been completely separated from the processes of labor, production, and the natural cycles of physical space. In the twenty-fourth-century, technology has also spread and intensified the human impact on nature, while at the same time allowing for a more sustainable civilization than human’s have probably every known. [24]

Of course, Roddenberry conjured other specific technologies to convey human mastery of the universe. In the episode “A Matter of Time,” the Enterprise travels to Penthara IV to assist in combating planet-wide cooling created by a terrestrial-dust cloud from a recent asteroid impact. Using its phasers to drill deep into the planet’s core to release carbon dioxide and increase the greenhouse affect to warm the planet, the crew creates a side effect of increasing the seismic activity of the planet and causing volcanic eruptions, threatening to send the world into an ice age. The crew decide to ionize the upper atmosphere in order to bring the climate back under control. The parallels of this episode to the 1991 context in which it was written are glaring. The early 1990s witnessed the intensification of environmentalist calls for action against climate change. In May 1985, scientists with the British Antarctic Survey shocked the world when they announced the discovery of a huge hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica. The disturbing discovery set the stage for an environmental triumph: the Montreal Protocol of 1987. [25] Against this backdrop, Roddenberry wrote episodes like this, commenting on Earth’s precarious late twentieth-century position and foreseeing a future controlled, managed, and maintained by human technologies. The “phasers” and “rays”

used to penetrate crust and saturate atmosphere, all call back to 1980s, Cold-War visions of American military superiority. The mention of carbon dioxide also connects this episode with Earth’s dire 1991 circumstances. Once again giving off a “colonial vibe,” Roddenberry’s Penthara IV story continues the history of capitalism unabated, uncritically analyzing the system’s flaws and naively predicting a utopia of unrestrained, infinite growth.

“Earth is the nest, the cradle, and we’ll move out of it.” [26]

While Gene Roddenberry created a vision of humanity’s future that was optimistic and confident, he was by no means oblivious to the peril twentieth-century civilization faced in the form of a changing climate and degrading environment. He was an educated pilot and police officer, steeped in the language of science and engineering, espousing humanist beliefs. His opinions on organized religion alone provide a lens to understand how he viewed the world. While also espousing human genius and resourcefulness, Roddenberry’s questioning of “the story logic of having an all-knowing all-powerful God, who creates faulty Humans, and then blames them for his own mistakes” markedly influenced his views on society and progress. [27] The stories he chose to tell in elaborating his Utopian future reveal a belief in the ability of capitalism to continue, in only restructured forms and in the resourcefulness of human invention, but he also acknowledges the environmental, social, political, and economic risks involved in human progress, as well as the limitations inherent in human nature and our desire to accumulate wealth and better living standards. In the end, with Star Trek, Roddenberry created an optimistic view of the future of capitalism that also recognizes the potential for crisis, catastrophe, and environmental and social degradation and conflict.

While the human ingenuity and technological prowess that created this utopia allows humans to live sustainably at relatively high levels of wealth, Roddenberry complicated his message with episodes like “Forces of Nature,” where warp capability creates instabilities in space and threatens human expansion through the galaxy, and also unjustly affects specific groups of people, threatening their living standards, and even their very existence. Here we see a flawed system akin to capitalism in its inevitable unsustainability. In other episodes, Roddenberry deals with other possible side-effects of science and technology with outbreaks of epidemic disease created by scientific research that threaten the lives of crew members. In “Unnatural Selection,” a team of scientists is researching organisms that affect human aging and accidentally create an airborne contaminant that greatly accelerates the aging process. After the disease has already killed an entire crew about the USS Landry, Chief Medical Officer, Dr. Pulaski, contracts the disease, setting off a long chain of events that almost ends her life. Seen in a more holistic way here, Star Trek: The Next Generation is a critique of capitalism. Roddenberry displays examples of “limits to growth,” systems technology cannot sustain, and negative environmental factors due to the drive for progress and accumulation. So although Roddenberry’s vision is “pro-growth,” and “cornicopic,” he still reminds us of the ultimate tension of modern human civilization: the accumulation of wealth and better living conditions versus building a sustainable, egalitarian society. He does not, however, offer a resolution to this tension, or provide a space in which humans can contemplate breaking free of the ecologically vicious cycle of capitalism.

Gene Roddenberry used specific characters and story lines to advance his ideas about the future, particularly the Borg and “Q.” The omnipotent, rascal-of-a-character, “Q,” is always a humbling presence for humans, questioning whether the human species is ready for space travel and involvement with the wider universe. Decidedly judgmental and “human” in his own right, “Q” serves as a constant reminder of our checkered past of technological and environmental destruction, calling back to our violent and discriminatory instincts. “Q” believes humans are not prepared for the power warp technology gives them. But Roddenberry, through Captain Jean-Luc Picard, allows his confidence in human ingenuity to show through. In the end, “Q” decides to allow the Enterprise passage through space, and even helps Picard save humanity from a spatial-anomaly threatening Earth. Although Roddenberry’s universe references a history of human and environmental violence, the character of “Q” serves to further his general idea that humanity can continue to accumulate wealth and better standards of living through capitalism, science, and technology.

The Borg represent technology and science gone wrong, the pure embodiment of the negative associations humans have with our creations. Half machine, half organic, the Borg show how technology can ultimately lead humans down dangerous paths – paths ending in empire, genocide, and a loss of our humanity. The Borg are controlled by a central intelligence, completely disconnected from any idea of self. They travel en mass throughout the galaxy, destroying other civilizations by “assimilating” them into the Borg collective, making the organic cybernetic in the process. The Borg’s message to their victims, “resistance is futile,” is a stark reminder of the dangers inherent with technology and capitalism. Unlimited growth is highly tempting for humans and our baser desires. Like with the Borg, Roddenberry is saying that once humans go down the road of infinite growth to build a more technocratic society, we will forever be in danger of veering towards “the Borg ideal,” where technology fully integrates with the biological and completely erases our humanity. A dark and pessimistic vision, this idea can be seen as an allegory for climate change or any other techno-apocalypse one can imagine.

The astute reader might ask: what about the Borg’s centralized nature, their monitored and controlled existence, and their lack of identity? Does this not sound much like communism? I would argue that, yes, the Borg seem to represent America’s communist foe during the Cold War. As a metaphor for communism, the Borg argue how technology and immoral political and social structures can germinate to create evil. When the Borg “assimilate” a planet, they consume everything. In two episodes, the Enterprise arrives at planets the Borg have passed through to find all life exhausted, no organisms left, all vegetation, water, soil, completely gone. Only the dry, rock shell of the planet remains. Here, the Borg-Communism connection is clear: communist governments lead to desolate landscapes. This example of Roddenberry’s use of the Borg complicates their use in his utopia. While in one sense they represent a critique of capitalism, they also can be seen as a scathing rebuke of communism, diluting any possible question of Roddenberry’s loyalty to the pro-growth ideal and infinite accumulation.

You might also question where society’s consumed resources go. During a vast majority of the show, we see little to no garbage, waste, pollution, or abandoned industry. In the end, I can locate only one clear example of the twenty-fourth century left-overs of growth. In the episode “Unification,” Will Riker leads the Enterprise to a Federation Decommissioned Ship Yard. In fact, it takes up an entire planet and it’s orbital space. Among thousands of asteroids, the Federation has deposited hundreds of decommissioned star-ships, some possibly a century old. The planet serves as a waste receptacle for the Federation, much as rivers served as “industrial sinks” to nineteenth-century cities. Star Fleet has created a unique, new environment made up of rocks, technology, and space. Here we see the argument of this article: the seemingly egalitarian, seemingly sustainable inter-galactic society brought to life in Star Trek can only be possible with vastly larger, more complex economic systems and energy regimes. These societies would also necessarily create enormous amounts of waste. On Star Trek, we are rarely shown the spaces human’s, or any other species for that matter, store or destroy their waste. Seeing these spaces would cast doubt on the idea of unlimited growth and harshly critique capitalism. Perhaps considering this in the context of the political and cultural turbulence of Cold War-era America can shed some light on why Roddenberry chose to create such a waste-less place. [28]

The topic of Donald Worster’s Shrinking the Earth is one of the most critical issues facing humanity in 2019. The idea of unlimited growth, infinite capital accumulation, and unrestrained natural resource use to support rising living standards across the globe, has brought our planet’s bio-systems to the brink of collapse, with water, land, and air cycles all threatened. We must reconsider the debates character’s in Worster’s book engaged in throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. There have always been Americans who question our religion of growth, but they have consistently lost the argument to their more capitalist, resource-hungry counterparts.

Seen in this light, Star Trek and the universe Gene Roddenberry created need to be analyzed within the framework of this question: should humans seek unlimited growth? Should we not look for sustainable alternatives to runaway capitalism? Why have “anti-growth” arguments failed since the industrial revolution? Are these environmental and economic values too intertwined with ideas of nation, manhood, and humankind’s divine right to stewardship over the earth to allow for any meaningful progress?

Roddenberry addresses these questions tangentially, for the most part, as the absence in his narrative of any recognition of the problems of growth reveals. Roddenberry created a technocratic society, built and controlled by expertise, scientific knowledge, and technological dominance. New technologies have allowed humans to once again avoid the difficult conversations around capitalism, resource scarcity, and environmental degradation. By omitting these volatile issues, Roddenberry makes a powerful statement: technology will allow humans to continue on the same path we have since the discovery of “second earth” and will allow humans to continue to accumulate wealth and raise their living standards. Nowhere in his universe, in direct or metaphorical ways, does Roddenberry question this basic assumption. Seen in the context of the Cold War United States, Roddenberry is telling Americans not to worry about scarcity, pollution, wilderness destruction, or loss of biodiversity. Technology and human ingenuity will push capitalism through the bottleneck of climate change and human society will appear on the side, in tact, sustainable, and more progressive than ever. Technology and human ingenuity created the egalitarian, peaceful, democratic society we see in the Federation of Planets in the twenty-fourth century.

Donald Worster’s “third earth,” the planetary escape route for continuing infinite growth, is an important part of understanding Gene Roddenberry’s utopia in Star Trek. Worster argues,

A new planet, if it came drifting our way, would throw that evolutionary process into disequilibrium, upsetting all that seemed solid and forever. Like Van der Donck, people would see to exploit the new environment, although some would prove more adept than others at doing so. Minds would begin to innovate and experience a burst of adaptive creativity. People would develop new technologies, invent new economies, and think new thoughts. A radical change in resource abundance might encourage a radical change in the structure of the human community, the organization of industry, the distribution of political power, and the relations between rich and poor. Religion might take a new direction. Ethics might be upended and revised. [29]

Go watch (or re-watch; shame on you) Star Trek and think of Worster’s words. You will find many similarities. Worster is describing what has occurred in Gene Roddenberry’s universe. We see warp drive and replicators, growth without money, the Federation, and the extermination of poverty on Earth (most likely through the exploitation of nature on distant planets). But Roddenberry’s reality is still difficult to grasp in 2019. How could we continue with a form of capitalism that has not questioned the idea of growth itself? How is it even possible to achieve such an equilibrium seen in Star Trek? Perhaps glimpsing, as Worster described, the “radical change” itself, the discovery of “Third Earth,”and the “burst of adaptive creativity” that followed would make Roddenberry’s utopia more believable. Or perhaps, our pessimism reflects more the fear and disgust many humans feel toward the “pro-growth” ideology in 2019. In either case, Star Trek, and other futuristic, science-fiction worlds, provide a unique way to ponder capitalism, the environment, and science and technology policy.

[1] http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/374304-it-isn-t-all-over-everything-has-not-been-invented-the. Accessed July 21, 2019.

[2] quotecatalog.com/quote/thomas-cole-nature-has-spre-LaDVP07. Accessed July 21, 2019.

[3] See Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frontier_Thesis) for a discussion of the American Frontier; and see Donald Worster’s Shrinking the Earth for a discussion of the importance of the New World in the idea of the frontier and second earth.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gene_Roddenberry; https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gene-Roddenberry.

[5] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/06/the-poetry-of-progress/. Accessed July 15, 2019.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gene_Roddenberry; https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gene-Roddenberry

[7] youtube.com/watch?v=7DSo8TnHv6Q&list=PLmA8N3lTnVI7SPoscPBz-jbrpbyn1TInV&index=7

[8] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 13.

[9] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 5.

[10] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 10-12.

[11] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 35

[12] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 20.

[13] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 31.

[14] Andrew, Thomas. Killing for Coal. pg. 231.

[15] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 35-42.

[16] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 116.

[17] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 120-132.

[18] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 143.

[19] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 151.

[20] Worster, Donald. Shrinking the Earth. pg. 163.

[21] http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/374304-it-isn-t-all-over-everything-has-not-been-invented-the. Accessed July 21, 2019.

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transporter_(Star_Trek). Accessed July 19, 2019.

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warp_drive. Accessed July 19, 2019.

[24] Mieke Schüller (2 October 2005). Star Trek – The Americanization of Space. GRIN Verlag. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-638-42309-0.

[25] https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/05/100505-science-environment-ozone-hole-25-years/

[26] http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/374304-it-isn-t-all-over-everything-has-not-been-invented-the. Accessed July 21, 2019.

[27] The Hollywood Reporter, Sept. 8, 1966.

[28] http://www.ex-astris-scientia.org/articles/qualor.htm. Accessed July 20, 2019.

[29] Worster, Shrinking the Earth. pg. 24.